Medalist is a story that overflows with vivid colors in two different animation styles and equally vividly colored characters. Both will kindle the production of your feel-good hormones, making the anime perfectly suited for rainy stay-at-home days. Thanks to straightforward character traits, the boys and girls can be easily compartmentalized, and their stories will thus be easy on your mind.

Inori, her coach Tsukasa, and their friends will do their best to make you crack a smile. That doesn’t mean that they don’t face setbacks, hardships, or challenges in the straining sport of figure skating. But, their effective navigation of this competitive world and swift resolution of problems will reassure you that everything will be fine in the end. If you are not looking for an intricate story or complex characters, season one of Medalist is the anime for you.

Yet, amidst the twists, twirls, and double axels, a few critical topics tiptoed quietly onto the glittering surface…

The Huntsman

It’s hard to believe that eleven-year-old Yuitsuka Inori, who trembles at the slightest hint of danger, is a lethal menace to earthworms near and far. Alas, she couldn’t help it. Apart from the fact that the unearthed creatures, wriggling in her hands fighting for their lives, soothed her anxious mind, she also needed them as payment. With a bag of worms in hand, she bribed the receptionist at the Lux Higashiyama ice rink to grant her entrance. That way, she could, despite a lack of parental approval and financial backing, secretly indulge in her passion: figure skating.

Unfortunately, not all grown-ups were kind enough to allow a child to use the ice rink in exchange for payment in kind. Tsukasa Akeuraji, a 26-year-old former professional ice dancer, couldn’t handle this kind of generosity. “I’m paying the entrance fee with my hard-earned money. I won’t let a kid skate for free!” Thus, looming threateningly over the tiny girl, he tried to confront her while she was putting on the hard-earned skates (I’m sure it wasn’t easy digging up all those worms). Inori was gripped with fear by the menacing demeanor of the adult and bolted; she dashed out of the bench area past the receptionist and skillfully slid down the outside stairs’ handrail toward her freedom. Tsukasa, the self-proclaimed rink security guard, was hot on her heels. He finally caught her—literally, at the last minute—when she fell off the wall of a building, which she chose as an escape route.

At first, Tsukasa had a heart-to-heart with the young culprit, telling her that such behavior could cause the rink’s bankruptcy. But, after spotting a textbook about figure skating, the conversation immediately turned to this sport. Despite the initial misgivings about Inori’s bartering, Tsukasa was soon amazed by her diligence. “I wanted to skate no matter what,” she told him, “but my mom says I can’t because I’ll get hurt.” Hearing about the girl’s unfortunate situation, Tsukasa counseled her to tell her mother properly that she wanted to skate. So, in addition to planting immense guilt in the girl’s heart, he also tasked her with an impossible mission. Afterwards, the two parted ways (for now).

Maleficent

Shortly thereafter, Inori’s mother came to the skating club with her daughter in tow to talk to the head coach, Takamine Hitomi. Takamine just so happened to be Tsukasa’s former ice dancing partner, and—it just so happened—he, too, was present when the duo arrived. The four of them sat down, but Takamine’s sales pitch was interrupted by the mother. She wouldn’t want Inori to go through the same hardships as her older sister, who was hurt during a figure skating performance. Additionally, Inori wasn’t good at school, so doing both would be too much for her. The mother concluded that Inori couldn’t catch up with those kids who started when they were five anyway. To Inori, who was watching girls younger than her slide and jump across the ice with ease, she said, “Look at how good they are. If you join them, you’ll only feel miserable.” Well, well, if this isn’t valuable advice…

Since the goal wasn’t merely to partake in a leisure activity—which is rarely the case in sports stories—the mother’s concerns were valid . Most (though not all) professional Japanese figure skaters started at 3-5 years of age. The Japan Figure Skating Instructor Association (JFSIA) recommends starting at age 3-4. If you want to become a professional figure skater, or if you are aiming to become an Olympian, starting early gives you a definitive advantage. Yet starting in your early teens isn’t necessarily too late.

Even after Inori gave her mother a demonstration of all the self-taught skills, followed by a passionate and tear-jerking plea that could melt even the stoniest of hearts, the mother’s conviction did not waver. She argued Inori was too old, skating was too risky, and the efforts were too unrewarding. She firmly believed that preventing her daughter from pursuing her passion was in the girl’s best interest. And nothing Inori said or did could change that. Fortunately, the child’s autodidactic efforts were not in vain, because she was rewarded by the Fairy Godfather, who did his best to fulfill her wish.

The Fairy Godfather

Listening to Inori’s desperate pleading reminded Tsukasa of his younger self and the rejections and discouragements he had to face because he wanted to start figure skating at the ripe age of fourteen years. He was confident that Inori wasn’t too old yet and that she had everything a figure skater needed: talent, ambition, and the utmost dedication. Convinced that she would improve rapidly if given a chance, he proclaimed heatedly, “I will coach Inori!” Waving his arms and clenching his fists as if casting a spell, he yelled, “I will get Inori to compete in Japan’s National Championship!!”

Finally, after this display of fiery passion not only by Inori but also by her future coach, the mother yielded.

One might wonder how Tsukasa intended to achieve this, especially since his coaching skills had yet to be tested. Tsukasa himself was in doubt about his teaching qualities. But, when a colleague told him that these skills were inside him all along and that he just needed to trust in his own competence, his journey of self-discovery and self-assurance ended (at least in season one).

With fierce determination and unwavering belief, the two carved a path through every hardship and setback on their way to victory. Tsukasa provided Inori with whatever she needed in any given situation at any point in time. He was her emotional support when she felt insecure—which was pretty much all the time. He calmed her nerves in an animal-friendly way, using the laces of his vest instead of having her torture worms. And, as a steadfast believer in her abilities, he took her seriously when she exclaimed, “I want to win a gold medal! At the Olympics!” How else could he have replied to such enthusiasm other than by promising to turn her into an Olympian? Tsukasa’s commitment as her coach didn’t end there! He showed the magnitude of his dedication when he ran into the darkest character of the series—the ‘Neo’ of figure skating Yodaka Jun.

Neo

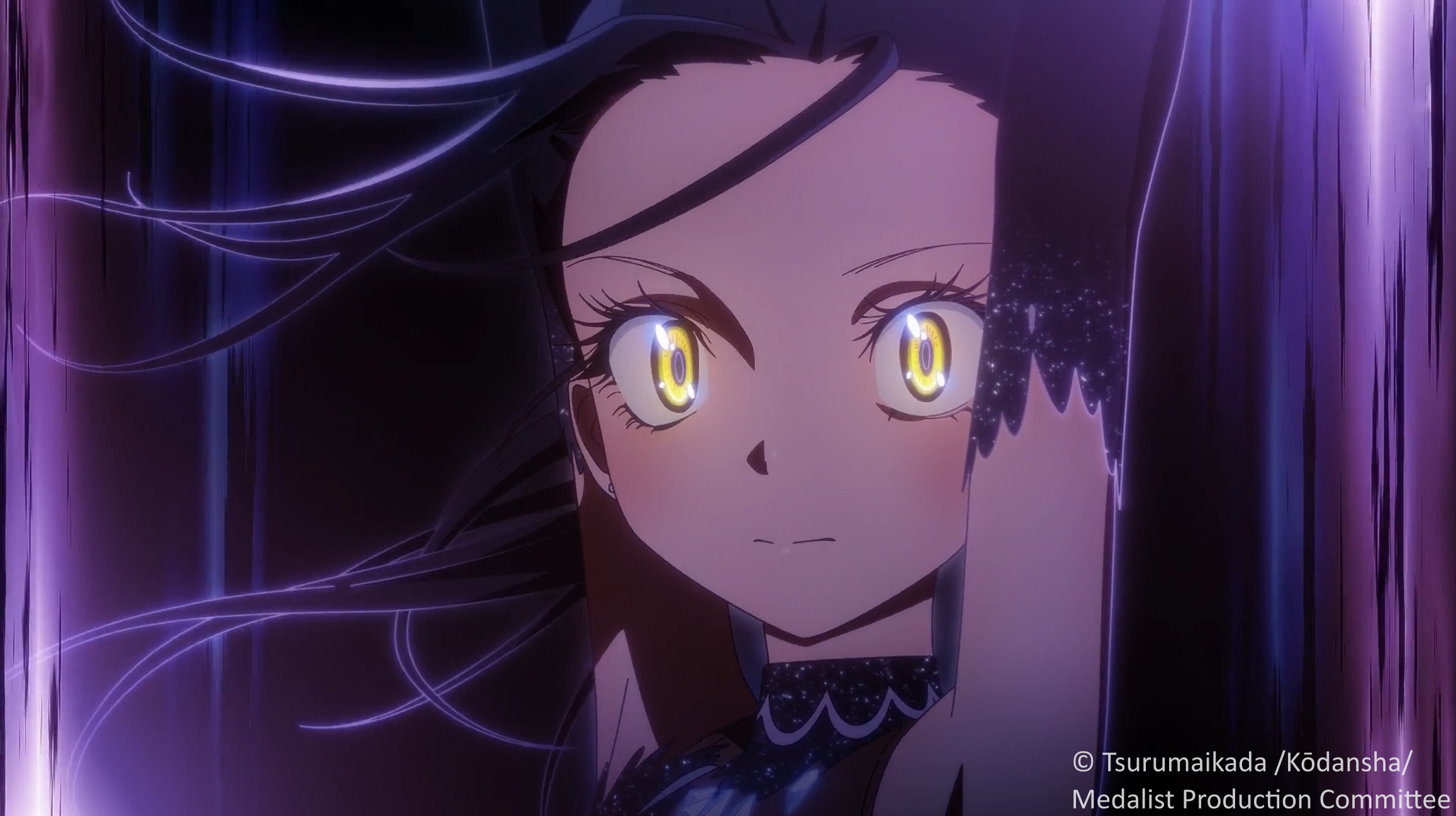

The first person to encounter the gloomy aura of this man in black was Inori. She crossed paths with him on the way to her first badge test. Outside the venue, she saw him smashing his ringing mobile phone against a wall in annoyance. The mistreated phone clattered to the ground, and with one last flicker of light, died. The dreadful experience of witnessing such violent behavior shook Inori to her core. And when the black-clad figure suddenly glanced at her, the piercing stare from the man’s golden eyes that cut through his dark sunglasses drained all the blood from her face. In this version, Neo might actually be the villain…

Neo alias Yodaka Jun is a former figure skater and he has already achieved what Inori is still striving for: an Olympic gold medal.

The two met again by chance at the Meikō Cup and were coincidentally joined by Tsukasa. While Yodaka struck Inori with fear, Tsukasa had deep respect for the achievements of the former pro skater and held him in high regard. He soon realized, though, that Inori’s ambitions turned them into rivals in coaching. How so? Well, besides wanting to be an Olympian, Inori also made it her goal to compete at eye-level against up-and-coming figure skating prodigy Kamisaki Hikaru. With this goal in her heart and mind, she not only created a rival out of a newly found friend but summoned another opponent: Hikaru’s coach, Neo-lookalike Yodaka Jun.

Confronted with Inori’s bold declaration that one day she would defeat Hikaru, Yodaka made it clear that as long as the prodigy was under his tutelage, such a victory was unattainable for Inori and her coach. This attitude set Tsukasa’s competitive courage ablaze, and he pulled out all the stops: “I don’t care who you are,” he shouted, “I will spend the rest of my life leading this girl to victory!”

After this heartfelt vow to carve their victories onto the frozen canvas until ‘death do us part,’ it was time to get back to practice.

But how did it come to be that Inori chose prodigy and top figure skater Hikaru as friend and rival?

The Beacon Of Light

With her black attire, black hair, and neon yellow-green eyes, Kamisaki Hikaru looks like Yodaka’s younger sister. But contrary to Yodaka’s grim demeanor, Hikaru is amiable and outgoing. The two girls met while crawling amidst some brushes. Inori was looking for worms to calm her nerves before her first badge test, and Hikaru was looking for… who knows what. After Inori complimented Hikaru on her dress, she promptly offered her friendship, and Inori accepted happily.

After the test, which Inori passed successfully, the mothers of other child athletes belittled Inori’s skating efforts. Hikaru heard this and was furious about these unfair insults. She grabbed Inori by the hand, dragged her onto the ice, and sped away. Initially awestruck by the speed, it soon fueled Inori’s competitive spirit, and the fledgling figure skater did her best to keep up. But when she saw Hikaru jump, she threw all caution out the window and unleashed the full range of her emotional volatility upon her new friend. At first, she stared wide-eyed in amazed disbelief at the perfection of the jump, then her voice started shaking with jealousy, and finally, tears of desperation rolled down her blushed cheeks as she shouted, “How do I jump like that!?” Hikaru was taken aback and couldn’t answer, which then sparked Inori’s anger. “I can’t beat you unless I can jump at my age!!”

When Hikaru still couldn’t provide a fitting response, Inori crawled toward the bewildered and retreating star skater. As all other things failed, she now tried to draw out Hikaru’s secret through hypnosis: “Teach me how to jump. Teach me how to jump. Teach me…” Finally, Inori’s eager advances caused them to topple over. With the physical shock of landing on top of the future skating star, Inori reverted to her insecure self and cried bitter tears, lamenting the huge gap in skill. Nonetheless, she swore to reach the prodigy’s level and compete against her. Luckily, this didn’t harm their friendship. Maybe by way of compensation, Hikaru let Inori in on another secret: Grown-ups are just big oafs and know nothing about kids.

Hikaru wasn’t the only one with such a critical view of adults. Inori’s two sidekicks, Miketa Ryōka and Sonidori Riō, had a rather low opinion about adults as well, particularly about their coaches.

Cat Girl

Miketa Ryōka is a feisty and short-tempered kitten-girl, hissing and clawing at others, even at her coach. The cat ears are a permanent feature, but when excited or angry, which was often the case, she would bare her canines and extend her claws until they pierced her gloves. Her playful, docile side was only revealed in her skating performance. When she was a little girl… actually, she’s still a little girl, but the flashback took us to a time when she was even younger. Anyway, when she was a little girl, she was misunderstood by adults, which nurtured her distrust and hatred for them. Never trust an adult!

When Miketa met Inori, she immediately took a liking to the sweet and innocent girl and completely monopolized her. When she wasn’t stalking her, Miketa dragged her around the arena like a stuffed animal. Unfortunately, the friendship shattered to pieces when Inori, rather than listening to a girl younger than herself, chose to stick to her coach. “Don’t you know you’ll get stupid if you listen to adults?” Miketa tried to convince her to change sides. But Inori wouldn’t be swayed, and Miketa, who then, in a fit of rage, ended the friendship and told her they would be rivals forthwith. Inori’s loyalty to her coach shielded her from further involvement in a potentially manipulative and abusive relationship. If you’re curious about how she became Inori’s sidekick after all, please watch the anime.

Grumpy Young Man

Riō, the son of the former figure skater and Olympic silver medalist Sonidori Shinichiro, is a reserved, somewhat grumpy, and introverted child. He rebuffed friendships with peers (Sōta being the exception) as well as help from his temporary coach, Tsukasa. Riō hit a dead end with his current skills, and no matter how much he trained, he just wouldn’t progress. Weighed down by his heritage and comparing himself to the exceptionally talented Hikaru and her coach Yodaka, the boy had pretty much given up on ever reaching, let alone surpassing, their level.

Despite his cool and collected demeanor, he was a sweet yet anxious child on the inside. He was much affected by Tsukasa’s enthusiastic and outgoing behavior as well as by the coach’s pinpointed advice. And thus, bit by bit, the young coach won the child’s heart. When Tsukasa performed Riō’s choreography, the boy observed him spellbound, with cheeks flushed and eyes widened in amazement. “Coach Tsukasa may have started late, but he never gave up on bettering his skills,” his former dance partner Takamine explained. “There was no way he would miss this chance. This tenacity is what got him to the All-Japan Championships.”

Rather than just encouraging the boy with words, Tsukasa showed him through his own path and his performance that Riō could also surpass his current limit if he would persist and believe in his own abilities. And so, the boy opened up to him and accepted his guidance. Haahhh, what a sweet happy end.

Groundhog Day

Riō, Tsukasa, and Inori aren’t the only ones who struggled with setbacks or performance plateaus. Most child athletes who were given individual screen time faced similar difficulties, and they all shared a common formula for success: believe in yourself and never give up. You started late? Give it your all, and you will succeed. Were you forced to take a break because of an injury? Keep at it, and you will succeed. Did you make a mistake and screw up the performance? Get back on your feet, and you’ll succeed next time. Is there someone better than you? Don’t give up, and you will surpass them. Like a broken record, this mantra was uttered by the kids and their coaches and was also woven into the story to deliver the message without words. Admittedly, this is nothing new for sports stories, but the fervor with which the ten- and eleven-year-olds expressed their unyielding dedication would put anyone with average commitment to shame.

“I will win!” “You will win!” “We will win!” The relentless chants kept echoing in my head and fueled a sense of future triumph within me. When the end credits of the last episode started to roll, I too was determined to never give up on my goals.

The Seven Sprouts

Besides the short-tempered cat girl, Miketa, and Riō, the grumpy, one-and-only boy athlete, there are five other female child athletes who are introduced halfway through the anime. They are easily distinguishable by hairdo, eye color, and clear-cut character traits. There’s the confident cutie Kamoto Suzu and her friend, the quiet and gentle pigeon-whisperer Yamato Ema. There’s the dopey and outgoing forest fairy Shishidō Seira and her clubmate, the bashful worrywart Kurosawa Miihi. Then there’s the aloof and prickly Koguma Ritsuki and, last but not least, the sleepy nap enthusiast Kitora Kanna. Ema already had the chance to show her persistence in the face of difficulties, and I suppose the others will also each get their time to shine.

The vibrant hues of the character designs and the glittering skating costumes flooded my field of vision with a plethora of colors. So, at first, I thought my overstimulated brain played a trick on me, but upon closer inspection, I realized that Shishidō Seira really did have a yellow star in her purplish eyes. Truly, she has the most unique eyes, but that doesn’t mean hers are the only ones worth peering into. Numerous extreme close-ups gave us plenty of chances to become engrossed in several characters’ dazzling eyes. Be it Hikaru’s lemon-colored, piercing stare, the calm air of Riō’s turquoise eyes, or the burning furnace of Inori’s imploring gaze—they all held me captivated.

Clash Of The Styles

Inori and Tsukasa are a perfect match. While Inori’s stubborn persistence gave Tsukasa courage when he was in doubt about himself, Tsukasa’s steadfast belief in Inori’s abilities gave her the confidence to continue to grow. Both showed their emotions unfiltered, and Tsukasa, in particular, wore his heart on his sleeve. This gave rise to an abundance of comic relief scenes, some of which were funny and entertaining; others were a bit too much—or too little—for my taste. In general, though, excessively exaggerated or easily predictable comedy makes up the lighthearted charm of this anime.

A little less charming was the clash of 2D and CGI animation—though I suspect I’m in the minority on this point. The “artful combination of both 2D and 3D animation techniques” is hailed on the world wide web as “a glimpse into how future anime productions can use CG…” This new hybrid animation style is supposed to add realism “without disrupting the anime’s overall aesthetic.” Personally, I felt quite disrupted when the visual experience I was thoroughly enjoying suddenly changed to glossy imagery, stiff, polished faces, and the distinct air of GCI. Even though the choreographies looked great, it took me a while to get used to the different style, and just as my eyes were adjusting, the performance ended, and with it, the brief excursion into 3D animation. I might have enjoyed the CGI appetizers a little more had it not been for the incessant monologues by skaters or bystanders. Hikaru alone was permitted a wordless appearance that allowed me to be engulfed by the music and mesmerized by her stunning eyes (and abilities).

All Magic Comes With A Price

Episode after episode, Inori was confronted with situations that gnawed at her confidence. Whenever a challenge appeared or a setback occurred, her anxiety and self-doubt flared up. Oftentimes, Tsukasa’s solid support and trust worked wonders, and soon she was back on the ice, as if feelings of insecurity and despair had never existed. At other times, Inori’s elaborate introspections lead to a renewed fighting spirit.

Medalist touches on mental stress for child athletes through Inori and the other kids. However, the anime’s bright atmosphere, predominantly humorous content, many comic relief scenes, and—most importantly—the children’s fervent intrinsic motivation greatly soften the impact of this issue for us viewers. When anxieties or worries surfaced among the young athletes, it was often portrayed comically with exaggerated expressions designed to make us laugh. And when a character truly struggled, like Ema, the focus shifted to the coach, and the story was told from his perspective.

The rinse and repeat of skating isn’t only mentally taxing; it can also lead to injuries. In figure skating, overuse injuries seem to be very common, though, of course, they aren’t the only ones. This, too, is addressed in Medalist, albeit superficially. Inori’s excessive practice led to shin splints, which simultaneously meant that Tsukasa either encouraged or allowed her to train beyond what is healthy. After this diagnosis, however, Tsukasa vowed that from now on he’d be focusing more on how to prevent accidents and injuries. He thus prescribed a summer’s rest for Inori to recover from the inflammation. Though not happy about the forced rest, she was determined not to stress over the skill gap with those who started younger than her and keep fighting, nonetheless. “I’ll keep believing that, late or not, I can fight my next fight exactly as I am.”

With this, the ‘boring’ and uneventful time of R&R was skipped, and the story continued after Inori’s recovery and jumped straight into the action at Inori’s second Meikō Cup.

The Light, The Dark, And The Hues

Medalist is a lighthearted sports comedy. At least in season one. Maybe Yodaka will cause the story to take a darker, more serious turn in season two. If you can’t get enough of Inori and her friends and you don’t want to wait for the anime to see how the story unfolds, you can always dive into the thirteen volumes (twelve in English translation) of the manga.

Assuming that the production studio won’t change its current M.O., Medalist could provide some ‘disruptions’—or not—with the dueling animation styles. I might watch the second season if I need a dose of bright colors during the dismal days of the next winter or if I want to observe cheerful characters easily doing away with difficult issues to ease my own everyday struggles.

Links:

Subscribe to never miss a deep dive into the exciting world of sports anime, manga, and manhwa!